Do No Harm

Ukraine is a country in intensive care of democratic transition, but it still remains the only hope of liberal democracy in the whole of Eastern Europe. The Dutch people now face a choice between helping to help treat it with reform or leave it in the cold.

Nederlanders, as a Ukrainian who has a thing for your country, I need to talk with you. I came to think of myself as an unapologetic Netherlandsphile: I speak some Dutch and had my fair share of disappointment with De Oranje’s losses in football tournaments. I had graduated from a prestigious Dutch university with cum laude distinction. Probably on top of my class of seventy Dutch and international students in our Master program on European Studies. I went sailing to the Oosterzee and put on orange for the flamboyant Koninginnedag street parties. I’m honored to call some Dutch people my friends. But the most important thing that I borrowed from your culture is speaking directly and honestly about (often uncomfortable) issues. This is exactly what I intend to do in the next dozen of paragraphs, so bear with me, alsjeblieft. Read More…

What docs reveal about Kyiv’s response to Crimea occupation

Today, the National Security and Defence Committee has declassified and published the minutes of the most important high-level meeting of Ukrainian leadership after the Maidan. Much of this information has been already discussed by analysts and the media; but some details are still curious to point out to understand the ensuing political debate in Ukraine and beyond.

On 28 February 2014, as Russia was occupying the Crimea with its troops, officials of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine (NSDC) had met in one of the rooms of Verkhovna Rada. As Oleksandr Turchynov, then a parliament speaker and acting president of post-Maidan Ukraine, himself pointed out, the discussion was held in unprotected premises, so the participants would probably be unlikely to cite too sensitive details.

What to do in Crimea?

- All the participants realized how fragile Ukraine’s position in the Crimea was, as many army servicemen and members of the riot police had deserted or joined the enemy.

- PM Yatseniuk mulled a political settlement with the self-proclaimed authorities in Crimea (fiscal decentralization, language concessions), but admitted Russia would not allow such a settlement. Interestingly, another participant of the discussion, Andriy Senchenko (an MP from Crimea, member of Tymoshenko’s party) openly contradicted Yatseniuk. Senchenko claimed that it would be wrong to “negotiate with traitors and separatists” and suggested some half-baked legislative changes instead.

- However, not all NSDC members seemed to even agree on the legal status of Russia’s collaborators in Crimea. Prosecutor General Makhnitsky, nominated by the right-wing-populist Svoboda party, claimed that the most his Office could charge Aksenov and Konstantinov with (Russian puppets in Crimea) was “illegal power grab”, not separatism. That nonchalant designation provoked Turchynov’s indignant outburst that they were “terrorists” and “separatists”.

- Some participants seemed more concerned with the internal threats to the authorities in mainland Ukraine rather than the Russian aggression in Crimea. For example, deputy PM Yarema (responsible for law enforcement) insisted on immediate arrest of a notorious Right Sector member as a way to show consolidation of power post-Maidan.

- In the end, Turchynov initiated a vote on the introduction of martial law in Crimea, but all the other NSDC members spoke against it. Yatseniuk claimed it would be tantamount to announcing war against Russia, which Ukraine could ill-afford. Apparently, Yatseniuk was a dove in that discussion with tacit support from his colleagues Yarema and Tenyukh. Tymoshenko also claimed that “we should become the most peaceful nation on Earth and behave like doves of peace”; her only proposal was “holding peace conferences” and writing addresses to Western countries.

- The then-head of the Central Bank Kubiv claimed that deposits were actively withdrawn from bank accounts in Crimea and Interior Minister Avakov explained that Russians created effective supply chains for the defecting Berkut riot policemen on the peninsula. No ideas were voiced on how to tackle these challenges.

Could the West help?

- Then-Defence Minister Tenyukh asked the NSDC’s authorization for full combat readiness of Ukrainian troops, especially the aviation. He was particularly wary of getting embroiled in Crimea to only be attacked by Russia in the north: Tenyukh opined that Russian troops could reach Kyiv overnight.

- PM Yatseniuk appeared quite pessimistic about Ukraine’s chances to get military assistance from any of the Western countries. No-one in the room appeared ready to contradict him on this. It was as if Yatseniuk totally monopolized the dialogue with international partners. With hindsight, such “monopolization” of external communication might have been hugely detrimental. For example, Yatseniuk also claimed that the US had “no position yet” after talking to US vice-president Biden, but he did not elaborate on how his office intended to change that.

- SSU chief Nalyvaichenko claimed that “Americans and Germans” asked Ukraine to refrain from any active steps, because their intelligence signaled Russia’s readiness to start ground operations against Ukraine in the east. Similarly, the then Foreign Minister Deshchytsia implied Visegrad-4 countries (Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic) cautioned him against drastic moves.

- Yulia Tymoshenko, released from prison just a week before, was also present at the meeting as a leader of a major parliamentary faction. Yet the first time when Tymoshenko actually entered the discussion was when Turchynov suggested that Ukraine could request joining the NATO. That’s when Tymoshenko declared that talking of “urgent NATO membership would provoke even bigger Russian aggression”. Turchynov had to calm her down that the discussion was about consultations with NATO, not public statements.

Threats from Moscow

- Right in the middle of the discussion, the Head of Russian Duma Naryshkin called Turchynov on the phone to “pass threats from Putin”, as Turchynov himself put it. Allegedly, Naryshkin warned that if a single Russian soldier in Crimea was killed, Russia would declare the Ukrainian leadership “war criminals”.

- In response to those threats, Turchynov suggested a massive mobilization and transfer of Ukrainian troops from the West and Centre to the Eastern borders. Tymoshenko interrupted Turchynov to claim that a massive panic would ensue as Ukrainians will see “tanks roll across their cities” (that intimidating statement turned out to be utterly untrue as the events in the next months would show).

- In the end, Turchynov was the only NSDC member to vote for announcing a martial law in Ukraine. Instead, the NSDC approved a 7-point resolution containing less divisive provisions.

PM Yatseniuk keeps his seat. For Now

During one of the Maidan rallies, now-Prime Minister Yatseniuk boasted his phony courage: “If [I have to take] a bullet in my forehead, then be it a bullet to my forehead”. That awkward phrase had become a political meme long before he was appointed a Prime Minister following the meltdown of Yanukovych’s regime at the end of February 2014. Yet it was during the parliament session on 16th February 2016, almost two years later, that his political demise seemed particularly close, as the Verkhovna Rada finally heard a long-anticipated motion of no confidence to his government. Although many observers and even MPs appeared sure there would be enough votes to sack Yatseniuk, the prime minister survived the no-confidence vote easily. So what has gone wrong?

Arseniy Yatseniuk: Give me another five minutes, it might be my last speech.

Volodymyr Hroisman: Why are you being so pessimistic?

The 158 Spartans

10 a.m. She had let her hair down and bought new glasses to look beautiful on this warm February day. Yulia Tymoshenko had prepared to partake in a public flogging and eventually a dismissal of the man who she thinks had betrayed her. Rumor had it that the night before the Rada hearing her party was the first one ready to give Prime Minister Yatseniuk a boot the next day.

To put a no-confidence vote on the parliament’s agenda in Ukraine, you need to get the signatures of 150 MPs, and the collection of MPs’ autographs started early in the morning. Boosted by curious cameramen’s attention and the growing list of signatures against Yatseniuk, Mrs. Tymoshenko had beamed with confidence. Little did she know that the tables would turn ten hours later.

As crowds of (to a great extent, paid) protestors grew outside the walls of the parliament, the 158 signatures were finally collected for putting the no-confidence on the Rada’s agenda in the afternoon. In this drama, the loaded gun has finally appeared on stage.

Ukraine’s Parliament Passed the Much-Needed 2016 Budget

On 24-25 December, when the world was awaiting Christmas, Ukrainian MPs endured a law-making 20-hour marathon. After passing some crucial changes to tax and procurement legislation on Thursday, the Rada adopted the 2016 state budget in the waking hours on Friday. Despite last-minute vote and a rather brief in-house discussion, a sigh of relief is in order: this budget package is much better than a lack thereof.

Adoption of a budget in the last days of December has become a Ukrainian political tradition of sorts. Many MPs usually have their suitcases packed, awaiting their winter vacations overseas, with only one box to tick. The urgency in past years stemmed largely from the inability to adopt local budgets without the state budget. This is less of a problem this year, as new legislation allowed for local budgets to be passed even without the central one.

This year, the IMF program has been looming large over discussions of the budgetary process. Mindful of some infantile MPs calling on postponing the review of the budget till January, ambassadors of key Western partners even had to remind the Ukrainian parliament of the need to pass an IMF-compliant budget before year’s end. These warnings seem to have been heeded: the Rada has passed the budgetary package that is in line with the IMF requirements.

Західні донори попереджають популістів Ради

Сьогодні одразу дві групи послів в Україні оприлюднили заяви стосовно де-факту зриву бюджетного процесу певними групами нардепів (лобісти “проекту” податкової реформи Южаніної, “Євро-оптимісти” і т.д.) за 10 днів до закінчення року.

Заява послів групи країн “великої сімки” чітко підтримує урядові проекти податкової реформи та бюджету й нагадує нардепам, що вони вже загрались у політику і забули про зобов’язання України перед Міжнародним Валютним Фондом http://ukrainian.ukraine.usembassy.gov/…/s…/g7-12222015.html (українською)

Заява послів скандинавських та балтійських країн (Швеція, Данія, Норвегія, Фінляндія, Естонія, Латвія, Литва) солідаризується з заявою послів “сімки” та делікатно підкреслює необхідність “фіскального балансу” нового бюджету:

http://www.swedenabroad.com/…/Statement-of-Nordic-Baltic-A…/ (англійською)

Ми опинились в абсурдній ситуації, коли частина Блоку Петра Порошенка по суті саботує діяльність Міністерки Фінансів, яка була делегована в уряд цією ж фракцією. Звісно, вони при цьому посилаються на внутрішньополітичні причини як доволі прагматичного штибу (турбота про долю малого бізнесу), так і відверто популістичного (скорочення видатків на чиновницький апарат і при цьому вимога збільшити фінансування дійсно потрібних, новостворених іституцій, таких як НАБУ).

Проте для наших міжнародних партнерів ці внутрішньополітичні розбірки в коаліції (цілком зрозуміло) мають другорядне значення. Їх можна зрозуміти: після публічного масажу статевих органів прем’єр-міністра нардепом та сеансів обливання водою між урядовцями на Раді реформ спостерігати за українською політикою вимагає неабиякого терпіння. Разом з тим, нагадаю, зрив вчасного ухвалення бюджету, який відповідає узгодженим з МВФ параметрам, може коштувати Україні призупинення програми кредитування Фонду, яке неминуче потягне за собою припинення всіх інших програм міжнародних донорів.

Тож вдумайтесь: найбільші західні донори в Україні сьогодні були змушені публічно застерегти українських нардепів, що не варто доводити країну до фінансового самогубства задля передчасного старту виборчої кампанії. Мовляв, слухайте, ми ж охоче даємо вашій країні гроші на виживання та реформи, але якщо ви знову “кинете” МВФ, нам це вже робити не вдасться. Якщо вже заяви зазвичай дуже обережних дипломатів не вправлять мізки “єврооптимістам” та іншим “експертам” з бюджетних питань, то я вже й не знаю, що зможе.

Тріумф Анджея Дуди: як зміна президента в Польщі вплине на відносини з Україною?

Анджей Дуда – молодий, харизматичний юрист з Кракова, про якого мало хто знав ще рік тому не лише за кордоном, але й у самій Польщі. Дуда є депутатом Європейського Парламенту від правої, консервативної партії “Право і Справедливість” (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), котра вже 8 років знаходиться у опозиції до правлячої в Польщі “Громадянської Платформи” (Platforma Obywatelska, PO). Деякі польські видання описували Дуду цікавим терміном “третьорозрядного члена ПіС”, натякаючи на його політичну недосвідченість.

У чому секрет несподіваного успіху? Анджей Дуда провів дуже ефективну виборчу кампанію, зосереджуючись на активних подорожах Польщею та розмовах з виборцями навіть у невеликих містах, а також активному використанню соціальних мереж (слідкувати за його дописами на Твіттері можна на @AndrzejDuda). Дуді вдалось обійти Броніслава Коморовського на 1% голосів у першому турі, попри те, що ще взимку усім здавалось нібито результат виборів визначено заздалегідь на користь діючого президента. Несподіваний результат виборів змушує оглядачів не лише в Польщі, але й закордоном уважніше поглянути на нового президента Польщі.

Міфи і реальність

Візьму на себе сміливість розвінчати кілька міфів про результати польських виборів, які поширюються в українських та західних медіа.

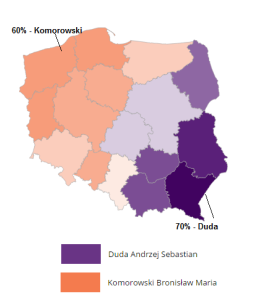

- “Вибори закріпили географічний поділ Польщі“. Це спрощений погляд на ситуацію. Так само як і у випадку з Україною, виборча карта голосування (див. малюнок справа) змушує західних коментаторів говорити про поділ Польщі. Дійсно, південно-східні воєводства (зокрема “сусідні” Україні підкарпатське та люблінське) у своїй переважній більшості підтримали Анджея Дуду (аж до 70%), а північно-західні надали перевагу Коморовському. Разом з тим, електоральний розрив у половині воєводств був незначним (блакитні і рожеві). Крім того, “гарні” карти не відображають більш суттєвих електоральних нюансів: Коморовський здобув більше голосів у великих містах (де рівень життя вищий) та серед більш освічених виборців, у той час як за Дуду проголосувало село й … американська діаспора. Цікаво, що явка на виборах – 55% – була на рівні з попередніми президентськими виборами, але багато східних округів були активнішими, що також зіграло на користь Анджея Дуди.

- “Польща посунулась вправо“. Результат виборів аж ніяк не означає активізацію праворадикальних сил та націоналістичних поглядів у Польщі. Головна причина перемоги Анджея Дуди: попри економічне зростання та добробут, поляки втомились від правлячої вже 8 років партії “Громадянська платформа”. Важливо також пам”ятати, що економічна платформа Анджея Дуди була більш популістичною, “лівішою” ніж у Коморовського: наприклад, Дуда наголошував на необхідності знизити пенсійний вік.

- “У Польщі відбувся антиєвропейський реванш“. Польща залишається однією з найбільш євро-оптимістичних країн у Євросоюзі. Вибір Дуди мав мало спільного з геополітикою. Натомість важливі демокрафічні та економічні тренди. Багато хто з молодого покоління втомився від “вибору без вибору” у країні з де-факто двопартійною системою, де електоральне поле поділене між “Платформою” та “ПіСом”. Попри закиди, що Дуда – це креатура під повним контролем Качинського, молодому кандидату вдалось вибудувати імідж нового гравця, який хоче “бути президентом усіх поляків”. У цьому сенсі польські вибори є частиною загального тренду у Центральній Європі: запит суспільства на свіжі, незаплямовані кон”юнктурою обличчя політиків (Андрей Кіска у Словаччині у 2014 році та Клаус Йоханніс у Румунії у 2015 році). Цей виборчий “тріумф” має слугувати уроком і українській еліті: у суспільстві, яке динамічно розвивається і вимагає змін у політичному істеблішменті, неодмінно виникне запит на “нове обличчя”, яке може отримати політичну підтримку як з боку політичної інертної молоді, так і старших консерваторів.

One Year of Poroshenko’s Presidency: Is the Public Love Gone?

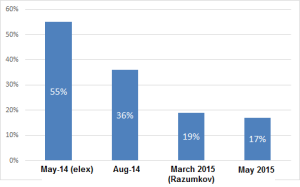

One year ago, Ukrainians went to polls to elect the country’s new, post-Maidan President. In breach of a long-standing political tradition in the country, Petro Poroshenko won in the first round with convincing 55% of the popular vote, with the runner-up, Yulia Tymoshenko, getting the modest 13% of the electoral pie. In another ground-breaking political change, Mr. Poroshenko gained the absolute or relative majority of the votes in all electoral precincts across the Ukraine-controlled territory of the country, except for the northern tip of Kharkiv region (which was loyal to a Party-of-Regions proxy). That resounding victory left Mr. Poroshenko with a strong mandate to lead the country in times of war and economic crisis, even though his constitutional functions were limited to foreign policy and defence.

Today, some media – UNIAN and 1+1 – made President a gift of sorts by unveiling the results of the poll carried out by TNS On-Line Track. According to the survey, 51% of Ukrainians are either fully or mostly “not satisfied with the President’s work”. It is important to note that those media are owned by the oligarch Igor Kolomoyskiy, who has had a conflict with the presidential team over the ownership of oil assets recently and whole political allies are in “soft” opposition to the President. However, even if taken with a grain of salt, those polls are likely to reflect public sentiment to the President one year after he was elected.

The reasons for the loss of popular support can be attributed both to grave external circumstances and Poroshneko’s own faults, most notably his mistakes in making high-ranking appointments. Many military casualties incurred in Donbas in autumn 2014 and winter 2015 stemmed largely from Russia’s decision to step up its army presence. Yet resignation of Ministry of Defence officials and the inclusion of army volunteers into the Ministry may have signaled that Poroshenko was ready to assume some responsibility. That belated change of course after running out of options seems to have become a hallmark of his presidency so far.

Those episodes of military escalation were both followed by controversial Minsk agreements, for which President also caught flak domestically. Positioning himself as a diplomatic heavyweight came at a cost: many in Ukraine, especially on the right, thought that the deals he had negotiated with Russians and their proxies were not in the country’s interests. Last but not least, Poroshenko is deemed to have postponed the fight against corruption for too long. His first appointment for the Prosecutor General, Vitaliy Yarema, has been widely criticized for ignoring or even obstructing persecution of the most visible corruption cases. The replacement in that position, Viktor Shokin, has been more agile in announcing new high-profile suspects than in sealing criminal cases in Ukraine’s notoriously-corrupt courts.

That said, 17% of Ukrainian citizens are “satisfied” with his performance in the presidential seat, according to the TNS poll. Granted, that figure shows substantial decrease in comparison to the approval ratings that Poroshenko had received last year (see the graph above). But losing two-thirds of his voters a year ago is only half of the story. As presidental rankings of previous presidents (especially, Viktor Yushchenko) show, things could have been far worse. Despite the severe economic and security situation in the country, Poroshenko has retained a loyal electorate core accounting for about one-fifth of the population, which he will rely on in the next local (or if things go rough, even parliamentary) election.

How Violent Beating of Protestors in Dnipropetrovsk was done

Local Officials Crack Down on Peaceful Protests in Dnipropetrovsk (Eastern Ukraine) on 26 January 2014

Key points

- The peaceful anti-government protest in front of the regional administration in Dnipropetrovsk was attacked by concerted forces of police and paid gangs of about 200 thugs;

- The authorities used a group of 50 provocateurs to simulate storming of the regional administration, only to use it as a pretext for a bloody crack-down on peaceful protestors nearby;

- There are clues that the criminals were hired and transported to Dnipropetrovsk by the people close to Oleksandr Vilkul, then-deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine and formerly a regional chief;

- These clashes were observed and allegedly “supervised” by Yevgen Udod, the head of Dnipropetrovsk regional council. Possible variants of spelling his name: Evgeniy / Ievgen / Yevhen Udod.

Struggle for Justice in Ukraine: No country for ordinary men

For the past two weeks, Ukraine has been swamped in a torrent of news stories unveiling the magnitude of the country’s police brutality and impunity. Policemen in Kyiv were accused of beating a student to death. Raisa Radchenko, an elderly civil rights campaigner in Zaporizhya, was incarcerated in a mental institution against her will, and only recently released under pressure from human rights groups. Stories like these make the headlines of Ukrainian news on a daily basis. Increasingly, these police abuses unleash a wave of resistance from the civil society, similar to protests in Turkey and Bulgaria, yet on a much limited scale. This movement has, however, received very little attention in European Union countries, both in EU foreign policy circles and general public alike.

‘Vradiyivka effect’

At the end of June news broke out that a 29-year-old woman had been severely beaten up and raped by three men, two of them policemen, in a Southern town of Vradiyivka. Amid the foot-dragging of law-enforcing authorities, a crowd of over 1000 townsmen besieged the local police station demanding to hand over the accused policemen. Under pressure from the protesters, the latter were arrested and some low-ranking officials sacked.

The events in Vradiyivka had ripple effects across the country, as they were followed by protests in a dozen Ukrainian towns. Read More…

Запаморочення від (євроінтеграційних) успіхів?

Деякі українські політологи, вслід за дипломатами, перекручують факти та дезінформують українську громадськість щодо прогресу України на шляху до підписання (або непідписання) Угоди про асоціацію з ЄС. Я наведу лише 4 міфи, які настільки нещадно експлуатуються українськими “експертами”, що їх варто проаналізувати детальніше неупередженим оком.

Нещодавня стаття політолога Костя Бондаренка (якого часто пов’язують з політиками Партії Регіонів) про перспективи підписання Угоди про Асоціацію між Україною та ЄС викликала у мене змішані емоції. З одного боку, хотілось щиро порадіти оспіваному євроінтеграційному прогресу України. Проте не вдалось: текст статті містив низку некоректних тверджень та алогізмів, які заслуговують на критичну відповідь. Оскільки мені довелось вивчати зовнішню політику Європейського Союзу у хорошому нідерландському університеті та досліджувати Угоду в найбільшому (і кажуть, найавторитетнішому) аналітичному центрі Брюсселя, цій невдячній справі півгодини приділю я. Тож по пунктам.